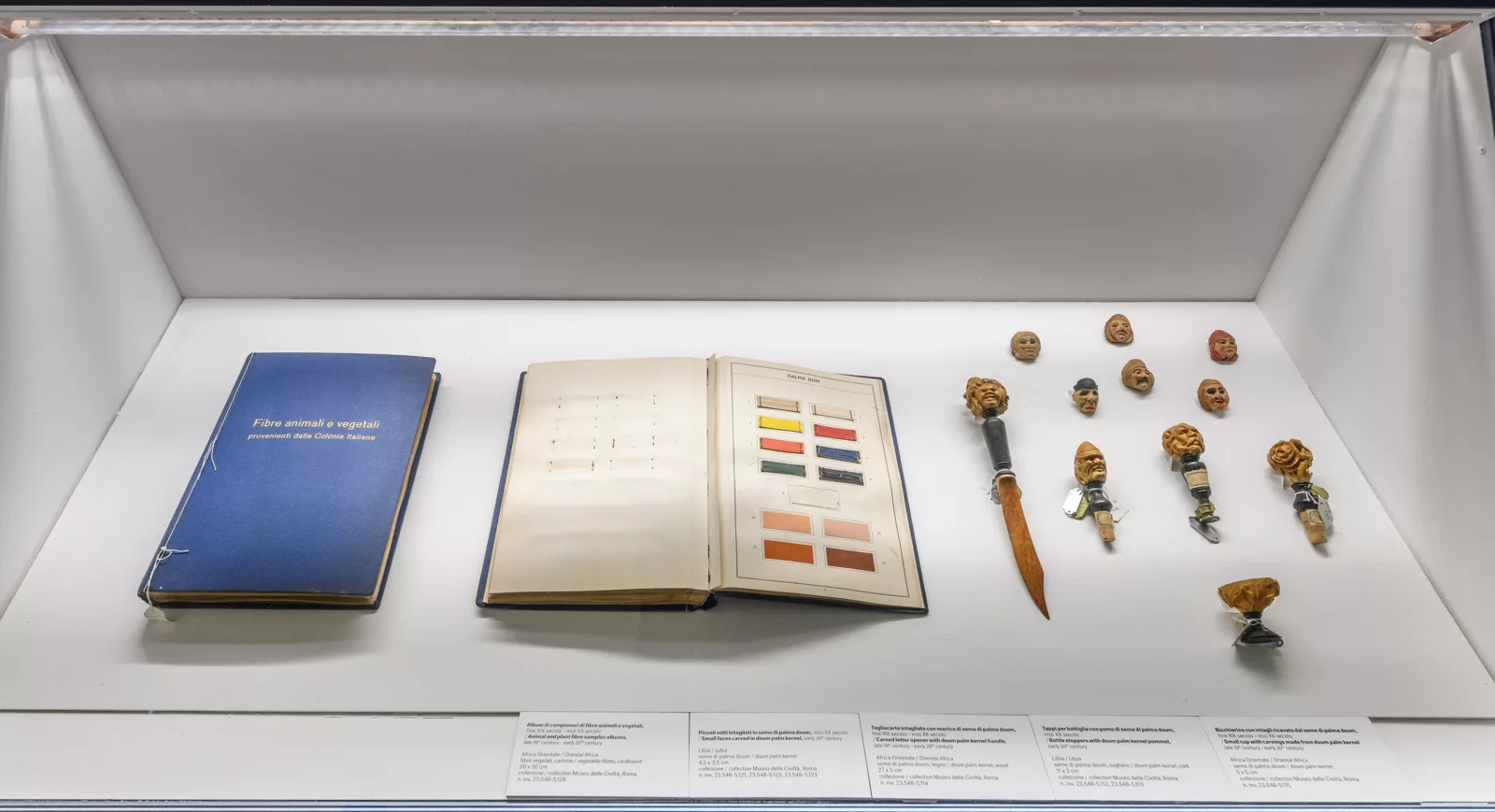

Within the Museum of Opacities exhibition (June 2023 – in progress) there are a number of materials related to the doum palm (Hyphaena Gaertn.), which are part of a larger collection of about 2,000 botanical, mineralogical, zoological, raw and processed commercial products exhibited in the “Mostra Campionaria” section of the former Colonial Museum in Rome. The paper presented here reflects on this case study, highlighting the practices of colonial extractivism and the predatory attitude toward colonial territories that characterized the colonial presence in Libya, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia.

by Rosa Anna Di Lella

Part 1

This glass vase with fibre of doum palm (Hyphaene thebaica) is part of a larger collection of around 2000 botanical, mineral, zoological, and commercial samples on shows in the Mostra Campionaria Section of the former Italian Colonial Museum of Rome (1914–1971). The Colonial Museum of Rome was an institution promoted by and related to the Italian Ministry of Colonies (1912–1937). It was founded in 1914, and opened for the first time in 1923 in the presence of Benito Mussolini. The main purpose of the Colonial Museum was of a propagandistic nature: knowledge of the Italian colonial expansion was to be shared with the Italian population, which, through the museum, was to acquire a “colonial awareness” and become well acquainted with Italian colonial enterprises as well as cultural, geographical, and economic aspects related to the territories occupied by Italy since the late nineteenth century. In the 1930s, the museum was moved to a larger purpose-built exhibition space. In parallel with the proclamation of Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana – A.O.I.) by Benito Mussolini on May 9, 1936 after the Italian conquest of Ethiopia, the institution was given a new name, the Museum of Italian Africa. The Museum closed for stocktaking in 1938, and remained closed during World War II to reopen only in 1947. In the 1950s it was renamed the ‘African Museum’. The essential exhibition framework remained unchanged, presenting, indeed, strong continuities in mission and museum display concerning the colonial period, ambiguous rhetoric and narratives, and nostalgic approaches to the Italian presence in Africa that led to its gradual decline. It was eventually closed in 1971. The collections of the former Colonial Museum of Rome were included in the Museum of Civilizations in 2017, after a long and complex institutional history marked by opacity and documentary omissions, propaganda missions and ambiguous purposes, openings and closures, relocations within the city of Rome, fragmentation of collections and documents. When the collections arrived at the Museum of Civilizations in 2017, they had been inaccessible since the early 1970s. A vehement claim was made by multiple researchers, the museum staff, and citizens interested in the collections to find out more about their history and the objects which had long been hidden: to start a journey of knowledge, acknowledgement, new accessibility and interpretation of the collections.

Part 2

In the context of this colonial institution, the Mostra Campionaria Section, opened in 1929, represented what must have been (in the eyes of the Italian colonizers) the most attractive commercial aspects of the Italian colonies, exalting the resources that the conquered territories offered both in terms of environment and human labour. Raw and processed materials, merchandise samples, seeds, oils, wood, furs, and minerals from Italian colonial domains were gathered in Rome for propaganda aims: to “educate” about and “raise awareness” of the economic potential for Italian companies operating in Libya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia, and to justify the human and financial losses related to military campaigns in East Africa and Libya between the late nineteenth century and the 1930s. Among the autochthonous botanical species represented in the Mostra Campionaria Section, the importance of materials related to the doum palm stand out in both the quantity and the variety of items collected. These range from seeds and leaf fibres to a large amount of finished products and discards garnered during processing stages. During the late nineteenth century, in the early stages of the occupation of Eritrea, the doum palm was subject to extraction for local exploitation or export. Considered the most important plant of the local flora for Italian enterprises, it was harvested as early as 1907 by the Società Cotonieri Milanesi (Society of Cotton Manufacturers of Milan) and exported to Italy for domestic production of buttons. Italian industrialists subsequently set up sawmill or button factories in Eritrea, and tried to grind the nut and the leaf of the doum palm to obtain flour for animal feed, fibres, cellulose, and alcohol. The plant and its components were the object of attention of Italian industrialists, politicians, and also scholars for its many uses. The famous Florentine botanist Odoardo Beccari (1843–1920) published taxonomic treatments2 on the doum palm in 1908 and (posthumously) in 1924. He had probably seen doum palm in 1870 while taking part in an expedition in Eritrea, alongside the explorer and zoologist Orazio Antinori (1811–1882), two years after the purchase of the port of Assab that determined the beginning of the Italian colonisation of Eritrea. Several articles and books on the doum palm were published until the 1930s, with the aim of popularising its uses. Several colonial exhibitions also devoted attention to this plant, starting with the International Exhibition held in Turin in 1911, one of the initiatives that celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the Unification of Italy. On this occasion, the Eritrean Colonisation Directorate’s exhibition showcased the colony’s local products: the doum palm was among the main attractions and described as a “providential”, “beneficial” plant that “offers precious resources, varied and remunerative uses. Today, the existing doum palm forest in Eritrea appears to be vast, but not long from now its limitations will be lamented, and its renewal and growth more carefully attended to” (Relazione Generale, 1913). Today, addressing how objects like a glass vase containing cellulose fibres come to be part of Italian heritage may foster reflection on the processes of despoiling of ecosystems perpetrated by the colonial apparatus. Now, the doum palm materials from the collection of the former Colonial Museum represent materially the imperialistic predatory behaviour toward colonies, and illuminate the propaganda context that characterized the museum, inviting thought on the colonial connections still alive in our museums (and societies) and the possible forms of remediation through the objects. The work of researching the colonial connections between Italy and the former colonial countries, starting with objects now preserved in the collections of the Museum of Civilizations, aims to deconstruct the narratives and make explicit the purposes that allowed the objects to be collected. Thus new narratives on the relationships between individual objects and their early contexts of production can be written, initiating collaborations with scholars, artists, and activists who bring alternative visions, backgrounds, and knowledge. The doum palm is an exemplary case in the Mostra Campionaria section, which we may consider a problematic database of biodiversity collected during Italian colonialism. The information in this repository could make it possible to initiate interdisciplinary research, considering that the Hyphaene genus is still poorly understood and evaluated and, moreover, the doum palm is subject to constant decline due to habitat destruction, drought, and overharvesting, which might inevitably lead to the loss of its gene pool.

This article has been published in the volume “Spaces of Cares. Confronting Colonial Afterlives in European Etnographic Museums” (Transcript, 2023), edited by Wayne Modest e Claudia Augustat, realized in the context of the European project “Taking Care. Ethnographic and World Cultures Museums as Spaces of Care” funded with the support of the European Commission. The entire volume is available at this link.

For the images in the gallery, the credits are from the National Central Library of Rome – Photo Library of the “IsIAO Library” – African and Oriental Collections Room. The photos depict Album no.210 – Società Anonima Industria Italiana Bottoni / Inventory: s.n.i. / Cover: hardback with faux-leather pattern and printed title in gold lettering / Dimensions (HxL): 25×35 cm / Number of sheets: 16 (of gray/green cardstock) / Number of photos: 15 / Printed captions under each photo / Conservation status: good; a few small tears on cover / Dates: s.d. / Places: Trescore Balneario / Photographer: Raffaello Bergamo / Printer: Raffaello Bergamo / Printing technique: silver salt gelatin on paper / Paid-up capital L. 1,500,000 / Headquarters in Trescore Balneario (Italy).” On each photo, embossed stamp: “Fotografia Raffaello Bergamo.” The album contains no items of Libyan interest. It is probably related to an offer of services to the Tripoli School of Arts and Crafts, of which there is a presentation poster inside containing a price list of the school’s products. Photos depict the factory (exterior and interior) and machinery.

Bibliography

O. Beccari, ‘Le palme ‘Doum’ od ‘Hyphaene’ e più specialmente quelle dell’Africa italiana’, Agricoltura Coloniale 2 (1908), 137–183

O. Beccari, Palme della tribù Borasseae (Florence, 1924)

G. Puglisi, ‘Le paginé d’un libro contabile’, Africa: Rivista trimestrale di studi e documentazione dell’Istituto italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente 5/9 (Sept 1950), 195–198

Le mostre coloniali all’Esposizione Internazionale di Torino del 1911, Relazione Generale, Ministero delle Colonie, Direzione Centrale degli Affari Coloniali, Roma, 2 (Jan 1913)

F.W. Stauffer et al., ‘A multidisciplinary study of the doum palms (Hyphaene Gaertn): origin of the project, current advances and future perspectives’, Saussurea, 47 (2018), 97–115