The article has been published in the volume “Spaces of Cares. Confronting Colonial Afterlives in European Etnographic Museums” (Transcript, 2023), edited by Wayne Modest and Claudia Augustat, realized in the context of the European project “Taking Care. Ethnographic and World Cultures Museums as Spaces of Care” funded with support from the European Commission. The entire volume is available at this link.

Reflections on A Collection in Turmoil. A Three-Day Workshop Held in September 2022 at MUCIV 1.

A Collection in Turmoil was an intensive workshop to explore the possibility of instituting a ‘permanent laboratory’ practice as part of the internal decision-making processes of the museum. It ran over three days in September 2022, was co-commissioned by Locales/Hidden Histories, was open to external participation and, crucially, included the museum staff. The workshop was focused on the intersection of transfeminism and decoloniality and invited a wide array of people with both for- mal and informal types of knowledge to participate. Trans writers, students, artists, botanists, film-makers, and researchers focused on the museum’s collection and on decoloniality took part in the workshop. This allowed for an openness towards the topics, and an approach that was less centred on discipline and academic conventions and relied more on cross-pollination between fields and ways of knowing (embodied, lived, doctoral, etc). This format proved successful in generating unexpected conversations and connections. It certainly required more patience, as some members knew the collection intimately, while others were seeing it for the first time.

Trans theorist and philosopher Paul Preciado’s work inspired the workshop’s conceptual framework. According to Preciado, we live in transfeminist times. Instead of seeking to re-identify the museum and ‘fix’ it in a new guise, I argue, following Preciado’s reflections, that processes of perpetual dis-identification are necessary. What happens if we treat the museum like a body? If we become aware of its constant metamorphoses, some of which we can guide?

The Workshop’s Structure and Tools

Embodied Knowledge

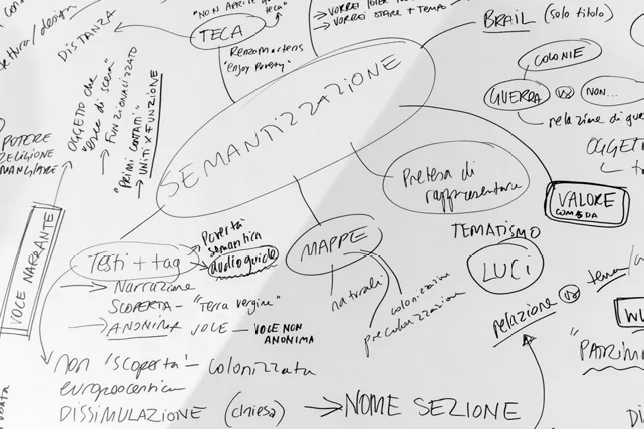

The workshop relied heavily on ‘image theatre’, a type of theatre developed in the 1970s by Augusto Boal as part of his Theatre of the Oppressed. It is a tool that allows participants to shape and experiment with ‘embodied knowledge’, meaning ways of knowing that are produced by the interaction of bodies, often in silence. The participants began by working on three themes, making group ‘statues’ that represented three possible, interlacing pathways for the collection: Rename, Repair, and Resist. The pathways alluded to objects in the collection being returned as reparations (Re- pair), histories attached to the objects being reevaluated and retold, objects renamed and re-semantisized (Rename) and finally, resisted – as a refusal of the museum’s own mechanisms and meanings (How does this collection exist at all? Is it possible to work with it/within the museum as an institution?). None of the possibilities excluded the other. As groups developed and performed their ‘statues’, we used a technique called the ‘multiple gaze of others’ to explore possible meanings, many unintended by the originators of the statues.

‘What do you see in this image?’

The responses to this question allowed us to make free associations based on the ‘sculptures’ (called ‘images’ in this method) by using the processes described above, exceeding what conversation alone can generate.

Guide Objects

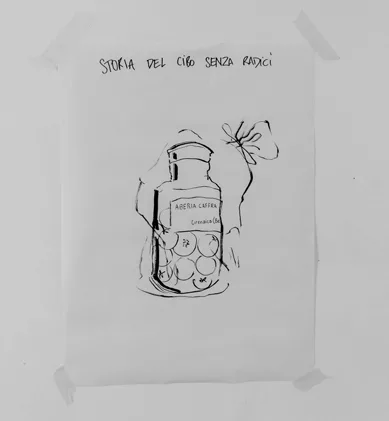

Another tool piloted by the group was the use of ‘guide objects’. Picking guide objects from the collections of the former colonial museum allowed us to a) form a bond with the collection and understand the ways researchers were exploring the objects (it was very interesting to see the index they inherited, bare and elementary in its description, making it hard to establish provenance) and b) to extrapolate an object and study it in depth, helping us derive meaning from ‘instances’ rather than what is commonly used to create taxonomies, assumed ‘groups’, or ‘wholes’.

Each participant was instructed to pick one or more objects and reflect on how the object ‘spoke’ to them, taking into account that their interpretation would be guided by their subjectivity. We then discussed how these objects would have been used originally by the colonial enterprise: to signify dominance, to showcase craft and agriculture as possible exports, to acquaint locals with busts of the Italian monarchy and fascist generals as ‘organizing’ figures, and to reassure colonists at home and abroad of the ‘sanctity ’ of empire. We explored exploding these narratives by creating different taxonomies that spoke differently about these objects, undoing their ‘patrimonial’ use.

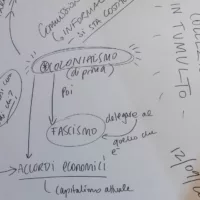

Workshop Scroll

From our very first workshop activity, we used a ten-meter-long paper scroll to record our conversations. One participant at a time was invited to write notes in real time when the group was called to participate in discussion during the exercises. The scroll became a central element of the workshop and elicited fascination, as it recorded – in different handwritings and different styles of note taking – the process of our coming together. At the end of the workshop, the scroll was unfurled on the floor and read out loud by participants who were invited to pick phrases to recite from it as they walked around the room.

Guidelines: Integration and Implementation

This section responds to questions of implementation and where this experience might lead with the prospect of the ‘permanent laboratory’ as a feature of the museum. What is a ‘permanent laboratory’? And what would it mean for the ‘permanent’ laboratory model to become ‘structural’? We have established that some of the methods developed for the inaugural workshop were: Political theatre in order to foster embodied knowledge, the use of ‘guide objects’ as single ‘portals’ into the collection, using the museum itself as a reflexive site – observing its displays collectively, recording the workshop on a scroll/ through material that can be shared publicly.

Political theatre is a guided experience led by a practitioner. It can be used to explore a) broad themes in line with the museum’s programming, b) personal narratives – the staff reflecting on their work, and therefore the institution reflecting its practices, and their implications. Its outcome is a progressive unpacking of assumptions and a forging of new connections through a practice that gathers people into intimate interaction. The museum could be said to be employing this strategy ‘structurally’ if it continued its commitment to engage staff in this practice as part of their paid working hours.

For this to work, it is necessary that the museum trusts this practice, and experiences it as generative, so that those who participate in workshops are offered time to develop ways to integrate their findings into their work.

The development of guidelines from this experience and from the use of guide objects should be used in developing taxonomies, displays, and labels. As work in this area is intimately linked to processes of re-semantization and the workshop it- self cannot offer enough time to develop precise models, part of the ‘permanent laboratory’ could be a working group tasked with developing and experimenting with in-depth methodologies, using the guidelines as a starting point.

Importantly, the institution of a ‘permanent laboratory’ within the museum should be accompanied by ways of sharing the results and processes of the lab with the general public.

1 In September 2022 the artist Adelita Husni Bey held the public workshop A Collection in Turmoil at Museo delle Civiltà. This workshop was curated by Sara Alberani and Marta Federici together with Valerio del Baglivo (of the project LOCALES) and in the framework of the Hidden Histories Project. The workshop was co-produced with the Museo delle Civiltà.